Copay accumulator programs have only one purpose; increase profits for payers. Patients don’t gain an advantage, nor do manufacturers. On top of that, providers face the difficulty of helping patients manage a process they don’t understand.

And somehow, the whole concept has gotten worse.

Patient Assistance Programs offered by manufacturers are intended to relieve the patient’s financial burden when filling their prescription. From the patient perspective, this is great. This blog takes a closer look behind the curtains to reveal how these programs are being abused by payers and hurting patients and manufacturers in the process. Here’s a teaser: original copay accumulator designs are the least of our concerns.

Background: Accumulators

The concept of copay accumulators was invented by payers. Under these programs, any money contributed by manufacturers through their patient support programs goes directly into the payer’s bank account. None of that money is credited towards the patient’s deductible, copay/coinsurance, or max-out-of-pocket (MOOP).

Impact

Patients temporarily benefit from manufacturer’s support even in the presence of accumulator programs. The pain occurs if the support program hits the annual dollar cap and the patient must start paying her deductible to continue therapy.

Anticipate the Impact on You!

Our free webinar offers information on how to analyze the impact of these programs and the opportunity to ask questions.

The Patient Assistance Predicament

Free Live Webinar

December 8, 2022 – 2pm Eastern

Let’s say the program offers $0 patient cost share. In other words, the manufacturer will pay the patient’s share of cost every month. These programs are usually capped, so let’s also assume our example has a $5000 annual cap. If the patient’s share is $1000/month, the program runs out of money in May. Suddenly, when the patient goes for a prescription refill in June, she is faced with a $1000 bill she did not expect. If she can afford to fill the prescription for the rest of the year, the payer will have collected $5000 from the manufacturer, plus additional money from the patient until she hits her annual MOOP.

Background: Maximizers

“Accumulating” copays wasn’t enough. “Copay Maximizer” programs were invented to pull the maximum value out of patient assistance programs even when the patient doesn’t need it. Payers could accomplish this by basing the copay/coinsurance of a drug on the value of the manufacturer’s patient assistance program instead of the plan’s benefit design.

For example, if the plan’s standard formulary sets our patient’s drug on a tier with a relatively low $50 copay, after the deductible the most a payer could collect over 12 months without a maximizer program in place would be $600 ($50 x 12 months). But if the manufacturer’s program had a maximum monthly benefit of $500 and an annual cap of $5000, the payer could change the copay for that patient to about $420 per month, enough to collect the full $5000 over the course of the year.

Impact

The patient benefits from the patient assistance program by not having any cost sharing for the drug, and, with a relatively low copay, the benefit lasts all year long. But let’s be clear: That benefit comes from the manufacturer’s offer of $0 copay, not from the Copay Maximizer program. Any payer that touts their programs “help patients afford their medicine” is simply being disingenuous. The point of a Copay Maximizer program is to pull as many dollars as possible from a manufacturer’s patient support program into the payer’s bank account. The only limit to these programs is the plan’s MOOP, which ends patient cost sharing for the remainder of the benefit year. Even though the payer may not credit the patient’s account, it can claim money on the patient’s behalf only while the patient has a cost sharing obligation; that obligation ends at MOOP.

Now It’s Worse

How could payers improve these programs to their benefit? Well, by eliminating the MOOP restriction we just mentioned. This would allow them to collect as much money as manufacturers are willing to offer patients, which can be far more than a typical plan’s MOOP.

A loophole in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) allows payers to accomplish this. Back in 2010, the ACA set an annual MOOP dollar limit for all policies sold in the U.S. In 2023, that limit is $9100. This means payers can only collect up to $9100 through these programs because that’s the end of the patient’s share of cost.

They’ve figured out a way to bypass this limit. MOOP applies only to Essential Health Benefits. In long-standing practice, the cost of any treatment that is considered “non-essential” doesn’t get accrued against a patient’s MOOP. So as long as a treatment is categorized as non-essential, there is no limit to the patient’s share of cost.

Here is an example from Duke Healthcare, working in collaboration with Express Scripts (ESI).

Duke has partnered with SaveOnSP, a vendor affiliated with ESI. Together, they have identified many specialty drugs as “non-essential”. There are over 300 drugs on the list. Here are some examples of what they consider non-essential:

- Enbrel – Which relieves arthritis so you can walk

- Eylea – Which helps you see where you’re walking

- Opdivo – Which treats your cancer if you had to walk to an Oncologist’s office

These are non-essential therapies?

All this twisting of intent so they can collect money intended for patients.

Look At This Math!

Let’s run through a math example using Enbrel to reveal what motivates payers, applying these data points:

- Enbrel retail price for one year of treatment: About $88,000

- Enbrel patient support: Patients pay as little as $5 per month

- Assume a 40% coinsurance based on the applicable formulary (on the high end, but not unheard of)

- Let’s add in a policy MOOP of $5000

- Assume the payer has the new-type Maximizer program that adjusts the patient’s cost sharing as high as possible (we still need a terrible name for this terrible development)

- Using the GoodRx price as an indicator, we estimate the rebate negotiated between the payer and Amgen (Enbrel’s manufacturer) to be about 35%.

If Amgen is willing to cover the 40% coinsurance, their patient support program will pay $35,140 over the course of the year. The patient contributes $60. Remember, by calling Enbrel “non-essential”, the $5000 MOOP doesn’t apply.

The 35% rebate over the course of a year equates to $30,800

Result: After all the contributions and discounts, the payer’s net cost for this $88,000 treatment is about $22,000.

Now here is a kicker: Duke is a 340B covered entity. They can buy Enbrel at a significant discount. Since we assumed a 35% rebate to the payer, we can assume the 340B price reflects at least that same discount. That means over the course of the year, Duke pays Amgen about $57,200 to acquire Enbrel. This represents Amgen’s gross revenue, which is much less than the retail price. Here is what the simple gross-to-net calculation for Amgen looks like:

Gross revenue: $57,200

Rebate to payer: $30,800

Payments to cover patient share of cost: $35,140

Net revenue excluding other discounts: -$8740

Yes, Amgen is paying $8740 for every patient who falls into this scenario.

This scenario assumes Amgen has capitulated to the payers. They have not. The terms of the company’s patient support program state the maximum value of the program can be changed based on the existence of a Copay Accumulator program of any kind implemented by the payer. This allows them to place a cap on the program’s value on a patient-by-patient basis. Touché!

What Does the Government Say About These Programs?

Depends on which government you ask.

Last year the federal government published a final rule, which states that these programs are legitimate. Rulemakers even removed a previous restriction that said the programs could only be applied when a branded drug had a generic alternative.

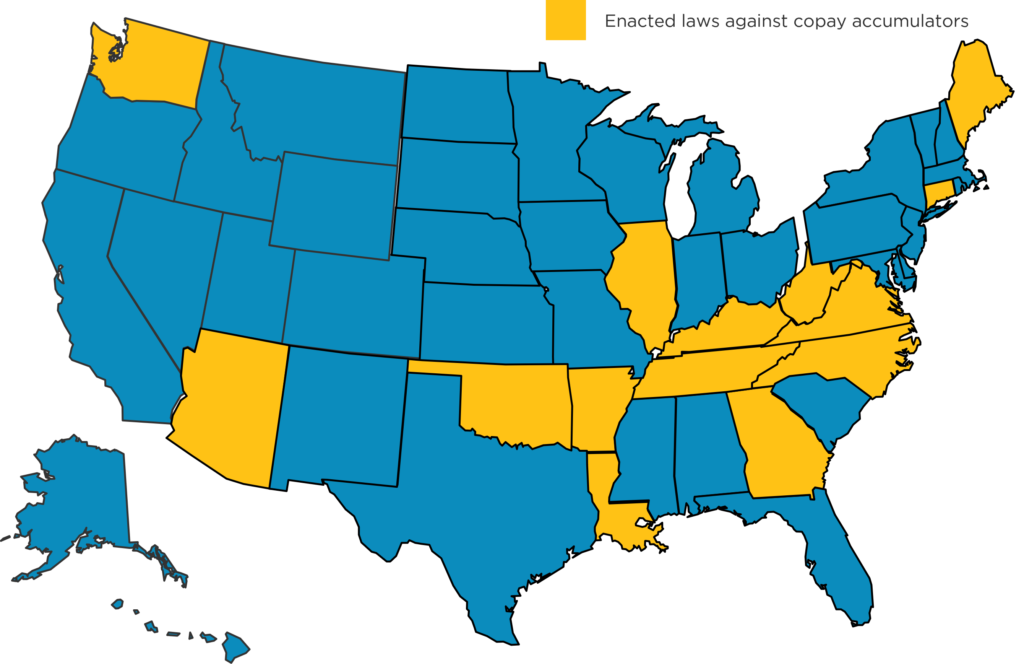

Many state governments, however, disagree. There are currently 14 states that have outlawed some or all aspects of Copay Accumulator programs. Those are shown here:

The restrictions vary by state. You can click here to see a state-by-state description of approaches used to protect patients from these programs.

Summary

Despite the fancy names marketed by payers, Copay Accumulator-type programs only benefit the payer. The patient doesn’t get any benefit they could not get from the manufacturer’s patient support program.

Manufacturers are almost forced to fight back, as their profits can vanish under many realistic circumstances. It is hard for a manufacturer to hide payments made on behalf of patients, as payers are actively looking for them. Credit cards or pre-filled debit cards are too obvious, Amgen’s approach seems like a good one!

Share Post:

Strengthen Your Customer Connections

Understanding the world prescribers are living in allows for more meaningful customer interactions. MAP Training Programs build your knowledge on marketplace trends impacting providers and the pharmaceutical industry today.

Achieve Company Goals

Bring teams up-to-speed on the latest market access trends impacting their unique selling environment.

Keep Your Finger on The Pulse

Subscribe to the Marketplace Blog to stay up-to-date on the latest trends impacting pharma

*required

Marketplace Blog

Trends in the Marketplace

“Negotiating” A Drug Deal with Medicare

[DISCLAIMER: This isn’t a legal analysis. We’ve simplified provisions in the law where we could while still describing the intent of the law] The newly-signed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that

Shopping for Healthcare Deals

New price transparency rules set by the government are an opportunity to save money. Not for hospitals, not for payers, but for you and me. Isn’t that a nice change

Are PBMs Actually Pharma’s Friends?

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) have received a lot of negative publicity lately. Here is some more: A new whistleblower lawsuit has opened another door that reveals more skeletons in the